Teachers, does your Confirmation Bias shut down student learning?

Having scolded teachers who politicize their classrooms in my post, “Teach Don’t Preach: politicizing the classroom is not just wrong, it’s bad teaching,” it begs the question of what to do with teachers who don’t know that they’re preaching not teaching and not just with politics.

As I noted,

Of course, curricular decisions are bound to teacher perspective. As History teacher, I value certain periods and concepts that other teachers may not care about.

As lessons are inherently bound to the teacher’s knowledge and interests, the challenge for an effective teacher is how to make that limited perspective beneficial for students — and, most importantly, without limiting them to it.

Confirmation Bias and the Teacher Preacher

As they say, to a hammer everything is a nail. Academics call it “Confirmation Bias,” a descriptor for the tendency of humans to see only what they’re looking for.

We all engage in Confirmation Bias on a regular if not daily basis. It often comes in the little things like searching for lost keys and finding something else you were looking for the week before. In this case, your “bias” to find the keys causes you to search out places or spaces that you didn’t think to look for when searching for that other object. You can also see how it works in this now-classic “Awareness Test” video.

In the hard sciences, Confirmation Bias manifests as experiments or observations that limit or ignore contradictory evidence or results. In the social sciences, Confirmation Bias occurs when an observer ignores or dismisses evidence or logic that contradicts an existing belief.

In the courtroom, trial attorneys regularly manipulate witness testimony and jury decisions by developing in them a Confirmation Bias towards the desired verdict, with the classic leading question being ,”Did you see the broken glass” as opposed to “Did you see any broken glass?” Asking if there was “any broken glass” is a neutral question, whereas “the broken glass” implies that there was broken glass which may trick the witness into “remembering” what was possibly not there. (Effective opposing counsel will object to such “leading questions.”)

A most prevalent form of Confirmation Bias comes, of course, in politics. Self-identity can be so wrapped around a political perspective or affiliation that simple facts become lies when they oppose our point of view. Even when we admit an inconvenient political truth, we easily get around it by diminishing it and convincing ourselves that it doesn’t matter for our guy because the other guy is worse, and so on.

If that makes any sense to you, please read my post “Teach Don’t Preach: politicizing the classroom is not just wrong, it’s bad teaching,”

For today’s post, however, the point is that Confirmation Bias operates with equal power, if quietly, in other aspects of teaching than straight out imposing a political opinion upon students.

Missing the Dancing Bear & Other Opportunities

Confirmation bias is not inherently wrong, as insight can result from ignoring the “noise” that others, if weighing all evidence equally, may not be able to filter, seeing the forest and not the trees, as it were. If you were too busy counting the number of basketball passes by the white team to see the dancing bear in the “Awareness Test” video, you may have missed out on bad moon walking technique while instead learning some cool passing moves. Your gain.

Because a narrow or overly broad perspective can be revealing in unique ways, I believe that one of the great benefits of Attention Deficit (ADD/ADHD) is precisely the lack of filters that can yield creativity and insight others may miss. The danger in only seeing things differently is that it becomes its own Confirmation Bias. Because my attention quickly goes to something else doesn’t excuse that I left the kitchen faucet on, it just means that my focus went elsewhere, for better or worse, and sometimes that “better” means an insight others could never conceive.

The Power of Perspectives

If the point of classroom diversity is to bring in additional perspectives for common learning, then confirmation bias contradicts the very purpose of diversity. A homogenous classroom yields great focus on its common purpose or point of view. It does not, however, challenge that point of view and at the expense of learning.

In his 1644 in Areopagitica, the poet and philosopher John Milton defended freedom of expression under the theory that since the absolute truth is unobtainable, only by allowing competing, if incorrect, perspectives, can mankind approach the truth. Should wrong expressions be suppressed, truth is obscured.

Back to the Classroom

I place the teacher that demands one conclusion or perspective among the tyrants that Milton rejected. My concern is that these teachers don’t realize what they’re doing.

Whereas the Socratic Method itself requires confirmation bias in the teacher whose job it is to direct the student to a conclusion, at least the Method allows for student exploration of ideas. Teaching that places the conclusion first not only denies students a path towards comprehension, it short circuits student thought.

I’m not a math teacher, but I know from working with students in our A+ Club academic support service that while there may be a single answer to a math problem, there are multiple paths to it, and by insisting upon that single path the learning of both the conclusion and the desired path are lost. So when I hear a student complain that a math or science teacher “doesn’t explain it in a way I can understand it,” I’m not necessarily hearing that the student isn’t learning, I may be hearing that the teacher is not offering an additional perspective or method that the student can better comprehend.

If Confirmation Bias is at work in math and science, then we have serious trouble in the humanities where it can take hold of an entire curriculum. The worst of it comes in politicization of the classroom, but it can infect a classroom even if the disease is more subtle, such as from a teacher’s limited points of view or content knowledge.

Let’s say that an English teacher wants students to identify with a certain character in a Shakespeare play. A flat-out requirement that students focus on that sole character will destroy the learning for all but the most compliant of students. The ban on other characters destroys student exploration and development of the conclusions the teacher wants students to adopt. Learning opportunities are lost in such an imposition.

The emotional bond to a learning outcome can be overpowering to a teacher, blinding that teacher to the Confirmation Bias that drives the learning expectation. At that point, we are not teaching, we are preaching.

Expanding our Confirmation Biases

We cannot escape our Confirmation Biases. We act on and develop perspective on what we already know and the experiences that have created our self-conception. Additionally, we often face institutional restraints, such as a school-wide ban on certain behaviors or outcomes. (I would suggest allowing classroom debate on such topics with the clear caveat that the school policy will not change regardless of student perspectives.) Still, we become better teachers, better mentors and guides for students when we can see past ourselves.

First, we have to listen. Next, we must never deliver conclusion before process.

We get there through active pursuit of new information, and when we as teachers can engage in a lively personal debate then we will become far more powerful teachers.

One of the worst kinds of Confirmation Bias comes from stagnation. When we stop learning we end up teaching the same thing over and over again and all we teach is only what we already know, which is inherently limited (see Milton). Worse, schools so often focus on pedagogy at the expense of content enrichment that teachers lose sight of developments in their own content areas that could otherwise expand and enrich their classrooms.

The solution is to place ourselves in a state of constant learning. If our consumption of information merely reinforces our existing Confirmation Biases, then we are learning — and teaching — nothing. It’s okay to read something you don’t agree with, and it will most likely affirm your own reasoned conclusions. But if we don’t expose ourselves to opposing or new ideas, we have no opportunity to grow intellectually and as teachers.

A Few Suggestions for Getting Past Preaching Not Teaching

- Consume the news not the headlines.

- Study your content not just its pedagogy.

- Avoid politics in your lessons and classroom (that does not mean that students should avoid politics, as that’s part of their growth which your job is to guide).

- Subscribe to content-oriented academic journals.

- Subscribe to general-interest journals

- Listen to podcasts on your way to and from work.

- Listen to your students.

My personal strategies include daily consumption of a printed newspaper, podcasts, and as many books as I can juggle at a time. Of course my choice of sources is biased according to my preferences, but I never stop consideration simply because I disagree.

This is all very time consuming. I had to drop my newspaper consumption from two papers plus a weekend third to a single daily and weekend paper, but even so every day I learn something new from that one newspaper that I can apply to my work with students and in my life in general. We must compromise for what’s possible, but we mustn’t ever let the undesirable guide the possible instead.

By becoming constant learners ourselves we will help our students to become owls not sheep — if only we ourselves are not the wolf in the sheep’s skin.

– Michael

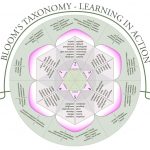

“Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain,” known more commonly as “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” identifies levels of learning from basic knowledge to higher-order thought that if used correctly can greatly empower student academic performance.

“Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain,” known more commonly as “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” identifies levels of learning from basic knowledge to higher-order thought that if used correctly can greatly empower student academic performance.

Procrastination is a disconnect between the NOW and the LATER. Overcoming the urge to procrastinate requires reconnecting with our own future. “Time Travel” can help bridge the NOW and the LATER.

Procrastination is a disconnect between the NOW and the LATER. Overcoming the urge to procrastinate requires reconnecting with our own future. “Time Travel” can help bridge the NOW and the LATER.

So how can we bridge the gap between students who only do as they’re told and those who learn only what they find interesting?

So how can we bridge the gap between students who only do as they’re told and those who learn only what they find interesting?

Is math just for math people? Are you just not wired for math? Well, you and your math-struggling student can celebrate Pi day, too!

Is math just for math people? Are you just not wired for math? Well, you and your math-struggling student can celebrate Pi day, too!

We hear it all the time. Students say, “I get it when my teacher shows it to me, but I can’t do it on the test.” Then parents tell us that their child “doesn’t test well.”

We hear it all the time. Students say, “I get it when my teacher shows it to me, but I can’t do it on the test.” Then parents tell us that their child “doesn’t test well.”

When students say they don’t “test well” or that they “don’t know how to study,” parents and teachers often respond with suggestions — and criticism — to, well, just “study harder.” Great. But what does “study harder” actually mean?

When students say they don’t “test well” or that they “don’t know how to study,” parents and teachers often respond with suggestions — and criticism — to, well, just “study harder.” Great. But what does “study harder” actually mean?